- antipodes

-

In these pages, the words "antipodes" and "antipodal" are used in a

non-standard sense, as defined in the page Antipodes.

- bipartite

-

A bipartite graph is one whose chromatic number is 2.

Its vertices can be partitioned into two sets such that every edge connects

one vertex from each set.

- blade

-

A "blade" comprises a vertex, an edge incident with that vertex, and a face incident

with both. It is the same as a flag but restricted to

two-dimensional things.

- C&D

-

In 2001, Conder and Dobcsányi listed "all regular maps of small genus"

C96, and assigned them unique identifiers. These

identifiers start with R for refexible orientable regular maps, C

for chiral orientable regular maps, and N for non-orientable regular maps.

The letter is followed by an integer denoting the genus, then a dot, then an

arbitrarily-assigned integer, and finally, in the case of dual pairs, a prime

to indicate the member of the pair with larger faces. Thus what I have called

S3:{7,3} has the C&D identifier

R3.1'.

These identifiers have the huge advantage that they are unique. Other naming

systems for regular maps lack uniqueness, see Schläfli

symbol below.

In these pages, I have extended these identifiers to regular maps of non-negative

Euler characteristic; so, for example, the cube has the identifies R0.2′.

- cantankerous

-

A regular map is cantankerous iff it has a cycle of two edges which reverses orienation.

"Cantankerous" was coined by Stephen Wilson in W89

to designate a certain class of non-orientable regular map.

canvas

canvas-

In these pages, a canvas is a "blank" diagram on which regular maps, of the

genus of that canvas, may be portrayed.

To the right is an example: a canvas for non-orientable genus 4. The small round

pink things are crosscaps.

chiral

chiral-

A structure is chiral if it has no mirror symmetry.

A chiral regular map in the torus is shown to the right.

A chiral object's full symmetry group is the same as its rotational symmetry

group; a non-chiral object's full symmetry group is generally twice the size

of its rotational symmetry group. But as objects embedded in non-orientable

surfaces can be reflected by translating them, their full symmetry groups are

the same as their rotational symmetry groups.

- chromatic number

-

The chromatic number of a regular map or other graph is the number of colours

needed to colour its vertices so that no two vertices with a common edge are

the same colour.

- chromatic index

-

The chromatic index of a regular map or other graph is the number of colours

needed to colour its edges so that no two edges meeting at a vertex are the

same colour.

- cover

-

A double cover of a regular map is another regular map having twice as many

vertices, faces, and edges. An n-fold cover of a regular map is another

regular map having n times as many vertices, faces, and edges. The

covering map will be in a surface with n time the Euler

characteristic of the surface of the map which it covers. This is

explained in the page double cover.

crosscap

crosscap-

Crosscaps in these pages are shown as on the right.

- dart

-

A "dart" comprises a vertex and an edge incident with that vertex. A dart

comprises two blades.

- diagonalise

-

Diagonalisation is a process which can be applied to any regular map that has

twice as many vertices as faces. It may yield another regular map, it may yield

something that is not quite a regular map, or it may prove impossible. The

process is described in the page diagonalisation.

- diameter

-

The diameter of a regular map or other graph is the greatest number of edges

it can be necessary to traverse to reach one vertex from another.

- digon

-

A digon is a face having two vertices and two edges.

Regular maps with digonal faces only exist in the surfaces of positive

Euler characteristic: the sphere and the projective plane.

- double

-

A double Petrie polygon, hole, or other circuit is one which traverses a set

of edges twice each before returning to its starting point with the same phase

it started in.

- dual

-

The dual of a polyhedron or other regular map can be formed from it by replacing

each face by a vertex, replacing each vertex by a face, and rotating each edge

through a right angle about its centre while keeping it in the plane of the manifold.

Thus the dual of the cube S0:{4,3} is the octahedron S0:{3,4}.

Duality is a symmetric relation: if A is the dual of B then B is the dual of A, hence

the name. See dual for more details.

- Euler characteristic

-

The Euler characteristic of a regular (or irregular) map is its number of faces plus

number of vertices minus number of edges. It is the same for all regular maps in a

particular surface (and for the irregular maps, so long as the faces all have the

topology of a disk).

See Wikipedia for

more information.

- Eulerian

-

An Eulerian path is one which traverses every edge of a graph exactly once, as in the

bridges of Königsberg.

An Eulerian circuit is one which traverses every edge of a graph exactly once, ending

on the vertex where it started.

A double-Eulerian circuit is one which traverses every edge

of a graph once in each direction, ending on the vertex where it started.

See also Hamiltonian.

- face adjacency graph

-

A graph showing, for a regular map or similar structure, which of its faces

adjoin which. It is the underlying graph of the dual.

- face multiplicity

-

In any one regular map, the number of edges that can be shared by any pair

of faces can take at most two values, 0 and mF. mF is known as the "face

multiplicity". See also vertex multiplicity.

- flag

-

"Flag" is a general concept used in the study of polytopes. For a polyhedron,

it comprises a vertex, an edge bounded by that vertex, and a face bounded by

that edge. In general for a polytope, it goes on to comprise a polyhedron

bounded by that face, a polytope bounded by that polyhedron, etc. The concept

extends naturally to regular maps. In two-dimensional structures, flags are

also known as blades.

A polyhedron or other regular map has four flags for each edge.

- full symmetry group

-

The set of all the rotations and reflections which can be applied

to an object so as to leave its appearance unchanged forms a group.

This is called its full symmetry group. See also "rotational

symmetry group".

If the object is a regular map, then its full symmetry group has four

times as many elements as the object has edges.

- genus

-

The genus of an orientable manifold is the number of "handles" you need to

stitch onto a sphere to make it. For instance, the sphere has genus 0 and

the torus has genus 1.

In these pages, the genus of an orientable surface may be designated

by Sn, with the sphere being S0, the torus S1, etc.; and that of a

non-orientable surface by Cn, with the projective plane being C1,

the Klein bottle C2, etc.

The genus of a group is the least genus of any manifold on which its

Cayley diagram can be drawn without the arcs crossing.

- girth

-

The girth of a graph is the number of edges in the smallest cycle. For a

regular map it cannot exceed the number of edges of each face.

- half-edge

-

The term "half-edge" is used here for a pair of adjacent flags. These flags

may share a vertex and an edge, or share an edge and a face, either way there

are two half-edges per edge.

A regular map is edge-transitive if any edge can be mapped to any other edge.

It is half-edge-transitive if any edge can be mapped to any other edge with

the edge either way round.

- Hamiltonian

-

A Hamiltonian path is one which visits every vertex of a graph exactly once,

using no edge more than once.

A Hamiltonian circuit is one which visits every vertex of a graph exactly once,

using no edge more than once, and ending on the vertex where it started.

A double (n-fold) Hamiltonian circuit is one which visits every vertex

of a graph exactly twice (n times), using no edge more than once, and

ending on the vertex where it started.

See also Eulerian.

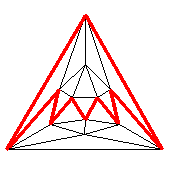

hole

hole-

A hole is a polygon found in a regular map by travelling along its edges,

taking the second-sharpest left at each vertex. This is only of interest

if the regular map has more than three edges meeting at each vertex.

An octahedron with a hole highlighted in red is shown to the right.

In these pages, we regard an octahedron as having six distinct holes.

Some writers identify pairs of holes that comprise identical sets of

edges, and therefore consider that an octahedron has only three holes.

See also Petrie polygon.

When we write of an nth-order hole, or an n-hole, a 1st-order

hole is what is usually called a face, a 2nd-order hole is what is usually

called a hole, a 3rd-order hole is found by taking the third-sharpest left

at each vertex, etc.

- hosohedron

-

A hosohedron is any regular map, in the sphere, with exactly two vertices.

- isogonal

-

A map is isogonal if it is vertex-transitive.

g03

- isohedral

-

A map is isohedral if it is face-transitive.

g03

- isotoxal

-

A map is isotoxal if it is edge-transitive.

g03

- lucanicohedron

-

A lucanicohedron is a quasiregular map, derived from a

hosohedron. The name derives from a fancied resemblance to a string, or

loop, of sausages: The Greek for sausage is

λουκάνικο.

- lune

-

A lune is a two-sided face, also known as a digon.

- multiplicity

-

The vertex-multiplicity of a regular map is the number of edges connecting

those pairs of vertices that are connected by at least one edge.

The face-multiplicity of a regular map is the number of edges shared by

those pairs of faces that share at least one edge.

- noble

-

A map is noble if it is vertex-transitive and face-transitive

but not necessarily edge-transitive. g03

- Petrie dual

-

The Petrie dual of a polyhedron or other regular map is the regular map whose

vertices and edges correspond to the vertices and edges of the original, and

whose faces correspond to the Petrie polygons of the

original. It is sometimes shortened to the portmanteau word "Petrial".

Petrie duality is a symmetric relation: if A is the Petrie dual of B then B is the

Petrie dual of A. Also, the Petrie dual of the dual of the Petrie dual is the dual

of the Petrie dual of the dual. See

Petrie dual for more details.

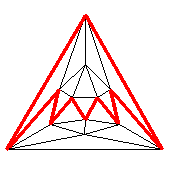

Petrie polygon

Petrie polygon-

A Petrie polygon is a polygon found in a polyhedron or other regular

map by travelling along its edges, turning sharp left and sharp right

at alternate vertices.

A cube with a Petrie polygon highlighted in red is shown to the right.

A Petrie polygon is a polygon found in a polyhedron or other regular

map by travelling along its edges, turning sharp left and sharp right

at alternate vertices.

A cube with a Petrie polygon highlighted in red is shown to the right.

If you have embedded the structure in 3-space, you will find that its

Petrie polygons are skew.

The concept of holes and Petrie polygons can be generalised, as described

in holes and Petrie polygons.

-

polyhedral map

-

A polyhedral mapB97

is such that the intersection of two distinct faces is one of

- empty

- one vertex

- one edge

Thus for example

{4,4}(2,1),

shown to the right, is not a polyhedral map: the intersection of two

of its distinct faces is an edge and a vertex.

Thus for example

{4,4}(2,1),

shown to the right, is not a polyhedral map: the intersection of two

of its distinct faces is an edge and a vertex.

In these pages, regular maps which are known to be polyhedral maps are

indicated by  , and those which are known

not to be polyhedral maps are indicated by

, and those which are known

not to be polyhedral maps are indicated by  ,

,

- portray

-

These pages portray regular maps as sets of faces, vertices and edges

in diagrams which generally also have pink sewing

instructions, showing how the diagram is to be assembled into the

required manifold. Such a diagram, before it has had a regular map

portrayed on it, is described as a canvas.

- presentation

-

A presentation of a group is a way of specifying it by means of generators

and relations. You can learn more from the Wikipedia article on

group

presentation. The presentations given in these page for full symmetry

groups are triangle

groups, taken from the work of Professor Marston Conder

c09.

- pyritify

-

Pyritification is a process that converts a regular map into a larger

regular map by dividing up each of its faces in the same way. It is

explained in the page pyritification.

- quasiregular

-

In these pages, a quasiregular map is like a regular map except that it

is not quite regular, having faces of two shapes. Quasiregular maps are

analogous to

quasiregular

polyhedra. One can obtained by rectification of any

regular map which is not self-dual.

- rectify

-

Rectification is the process which takes a regular polyhedron and shaves down the

vertices so as to form new faces. It is described in the Wikipedia article

rectification.

It is of interest to us because the rectification of a self-dual regular map yields

another regular map. Each vertex becomes a face, each face remains a face, and each

edge becomes a vertex. If the original was {p,p} with q vertices, q faces and pq/2

edges, then the new regular map is {p,4} with pq/2 vertices, 2q faces, and pq edges.

It is still in the same manifold. This is described more fully under

rectification.

- regular

-

A "regular map" is an embedding of a graph in a compact 2-manifold such

that

- the 2-manifold is partitioned into faces,

- each face has the topology of a disc,

- its rotational symmetry group is dart-transitive:

for any two darts, there is a rotation

of the whole thing that takes one dart to the other.

Grünbaum defines regular as meaning flag-transitive. g03

- replete

-

A regular map is said to be replete if there is a rotation that fixes

one face but not all faces, and a rotation that fixes one vertex but

not all vertices.

- rotation

-

Rotation is used in these pages for the operation of moving a regular

map continuously while keeping it embedded in its manifold.

- rotational symmetry group

-

The set of all the rotations which can be applied to an object so

as to leave it appearance unchanged forms a group. This is called

its rotational symmetry group. See also "full

symmetry group".

If the object is a regular map embedded in an orientable manifold,

then its rotational symmetry group has twice times as many elements

as the object has edges. If the object embedded in a non-orientable

manifold, then its rotational symmetry group is the same as its full

symmetry group.

- Schläfli symbol

-

A simple Schläfli symbol has the form {G,H}. The first number

specifies the number of edges per face, the second number specifies

the number of faces meeting at each vertex. Thus the Schläfli

symbol for the cube is {4,3}.

A Schläfli symbol can specify a stellated polyhedron, by using

non-integers. {5/2,5} is the small stellated dodecahedron, with five

pentagrams meeting at each vertex, and {3,5/2} is the great icosahedron,

with "two-and-a-half" triangles meeting at each vertex, i.e. its

vertex figures are pentagrammal. Stellated polyhedra are not

considered in these pages.

This can be extended to polytopes. The Schläfli symbol for the

600-cell is {3,3,5}. The 3,3 specifies tetrahedron; the 5 specifies

that 3 of these meet at each edge. But in these pages we are only

concerned with polyhedra, having two main numbers in the

Schläfli symbol.

If we are only concerned with genus-0 regular maps (regular polyhedra),

a simple Schläfli symbol of the form {G,H} is sufficient to specify

a polyhedron. But if we look more broadly, more numbers may be used,

to disambiguate. Here are some examples.

- {4,6|4} specifies a polyhedron with six squares meeting at each vertex.

The 4 after the | specifies that its holes have four

edges. This is an infinite polyhedron of infinite genus: it can be seen

in the first picture in the Wikipedia article

Regular

skew polyhedron.

- {7,3}8 specifies a regular map with three heptagons meeting at

each vertex. The single subscript 8 specifies that its

Petrie polygons have eight edges. We have a picture

of {7,3}8, it has genus 3.

- {6,3}(2,0) specifies a regular map with three hexagons meeting

at each vertex. There are infinitely many regular maps designated by

{6,3}, all of genus 1. The bracketed two-number subscripts specifies one

of these. Unfortunately I use a notation different from that used by

ARM, although we both use bracketed

two-number subscripts. Where ARM writes {6,3}(s,0) we write

{6,3}(s,s), and where ARM writes {6,3}(s,s) we

write {6,3}(0, 2s).

However, these various enhancements to Schläfli symbols are not enough

to make them unambiguous. {8,8|4}2

and {8,8|4}2 are different regular

maps, of genus 2 and 3 respectively, the latter being a double cover of the

former.

Therefore in these pages I disambiguate Schläfli symbols with a prefix

to indicate the genus where necessary. E.g. I will designate those

two polyhedra as S2:{8,8} and

S3:{8,8}. Where I omit the prefix

it should be clear from the context.

- Schlegel diagram

-

A Schlegel diagram portrays a regular map or other structure in a sphere,

on a finite flat diagram. It is a projection from the whole sphere to one

of the faces of the structure, using a point a short distance outside that

face.

In these pages, almost all the diagrams showing regular

maps on the sphere are Schlegel diagrams.

- shuriken

-

The full shuriken of a regular map is another map created by replacing all

its vertices by crosscaps and all its edges by four-valent vertices.

The half-shuriken of a regular map is another map created by replacing

alternate vertices by crosscaps. This is explained more fully in the page

on shurikens.

- side

-

A polyhedron does not have things called "sides", it has vertices, edges,

and faces. It is best to avoid using the term "side" in the context of a

polyhedron or other regular map, as some people use it to mean "edge" and

others "face". However, I use the term "side" for the "cut edges" of the

canvases on which regular maps can be portrayed.

- singular

-

A regular map is said to be singular if no pair of vertices has more than

one common edge, and no pair of faces has more than one common edge.

- skew polygon

-

A skew polygon is a polygon whose vertices are not coplanar. This concept is

only meaningful when the structure has been embedded in a space of more than

two dimensions. As these pages are concerned only with polyhedra in 2-spaces,

and not with their embedding in higher spaces, they do not use the concept.

- split

-

Splitting is a process that converts a regular map into a larger

regular map by replacing each vertex by a pair of vertices. It is

explained in the page splitting.

- stellate

-

Some regular maps can be stellated, by a process analogous to the stellation

of polyhedra. The process is described, and examples listed, at

stellation.

- symmetric graph

-

A symmetric graph is one which is half-edge transitive. There is more

information in the Wikipedia article

"Symmetric graph".

- transitive

-

A group which permutes a set is said to be transitive on that set if, for

any two members a, b of the set there is some operation of

the group which maps a to b.

Thus a map is said to be face-transitive if, for any two faces a,

b there is some operation of its symmetry group which maps a

to b. Likewise for vertex-transitive, edge-transitive,

half-edge-transitive, flag-transitive, etc.

- trivial

-

A regular map is said to be trivial if its faces have 2 edges, or

if its vertices have 2 edges, or if its Petrie

polygons have 2 edges.

- underlying graph

-

A regular map is an embedding of a symmetric graph in a surface.

The embedded graph is the "underlying graph" of the regular map.

- vertex multiplicity

-

In any regular map, the number of edges that can connect any pair of

vertices can take at most two values, 0 and mV. mV is known as the

"vertex multiplicity". See also face multiplicity.

canvas

canvas chiral

chiral crosscap

crosscap hole

hole Petrie polygon

Petrie polygon A Petrie polygon is a polygon found in a polyhedron or other regular

map by travelling along its edges, turning sharp left and sharp right

at alternate vertices.

A cube with a Petrie polygon highlighted in red is shown to the right.

A Petrie polygon is a polygon found in a polyhedron or other regular

map by travelling along its edges, turning sharp left and sharp right

at alternate vertices.

A cube with a Petrie polygon highlighted in red is shown to the right.

Thus for example

{4,4}(2,1),

shown to the right, is not a polyhedral map: the intersection of two

of its distinct faces is an edge and a vertex.

Thus for example

{4,4}(2,1),

shown to the right, is not a polyhedral map: the intersection of two

of its distinct faces is an edge and a vertex.

, and those which are known

not to be polyhedral maps are indicated by

, and those which are known

not to be polyhedral maps are indicated by  ,

,